- Home

- Anika Scott

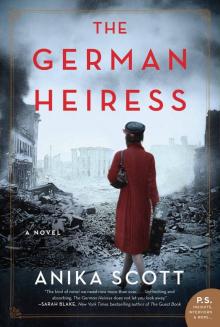

The German Heiress

The German Heiress Read online

Title page spread photograph © Historical/Getty Images

Dedication

To my daughters, Olivia and Amelia

Map

Map by Nick Springer / Springer Cartographics LLC

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Map

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Rock

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Wood

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Bats

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Water

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Air

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Dark

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Cracks

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Acknowledgments

P.S. Insights, Interviews & More . . .*

About the Author

About the Book

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

Everybody stole. Organized, they called it.

They organized coal off moving trains. They organized cars left alone in the streets. They organized pipes from houses where unexploded bombs nested on the roofs. Mostly, they organized food. Dug up fields and slaughtered cows. Hijacked trucks and robbed stores. Just that morning, Clara had read about a man who brained his friend for a slice of bread. The news sent the faintest prickle down her neck, and then she got on with her plans. Everybody organized one way or another.

Instead of sitting near the oil lamp like the other women, Clara lounged against the wall as far from the light as she could get. After sundown when the Allies restored power, the overhead lights would frost them all, highlighting eye color and birthmarks and all the other details she’d rather nobody concern themselves with. She touched the identity card in her pocket, testing the paper, the cheap card stock, then the smooth surface of the photo. The card was almost legal, issued by the town with signature and stamps.

According to the card, her name was Margarete Müller.

It was too dim to read in the waiting room, so the women sized each other up in silence. They were mostly mothers, gray-faced and younger than her, their children on their laps. As Margarete Müller, Clara did her best to blend in. Her coat was the same patched wool as the other women, her stockings mended just like theirs. A small hole she hadn’t gotten around to repairing was below the hem at her left knee. Still, the women stared. At the heels she’d chosen to wear despite the frost. At the hem of her skirt, slightly too high to be proper. At the dark red on her lips, makeup salvaged from the war. She knew what the women were thinking. Horrible, inappropriate, scandalous thoughts just because she was showing a little knee. Mothers could be so hurtful.

She tried to ignore them and watched the consulting-room door, still firmly closed, made of a thick oak that kept out the sound from the other side. When it opened and Herr Doctor Blum’s voice floated out, the women sat straighter, patting their hair and pinching color into their cheeks. He came out with a mother and daughter, the girl in dirty plaits, her skin as sickly pale as Clara’s not so long ago. His gaze passed over the waiting room, counting the patients, Clara guessed, calculating time, the amount of energy he’d have to expend to see them all. Since she started consulting him six months ago, he’d grown thinner, and now the bones in his face seemed to ripple under the skin.

He stooped in front of the girl, got right down to her eye level like no doctor Clara had ever seen—they were, as a rule, too arrogant for that—and he held his fist to the side of her head. Everyone in the room strained to watch as he gasped and seemed to find in the girl’s ear a sweets wrapper. Empty. Frowning like a clown, he let it flutter to the floor. Then he tried again, the fist at her ear, the gasp . . . and out came a peppermint in silver paper. The girl snatched it and bolted for the door, her mother batting her lashes at the doctor on the way out. Clara knew Dr. Blum well enough to know he’d try to ration his mysterious supply of sweets. Whenever he found some on the black market, he vowed to give them out slowly over a week or more so the sick children had something to look forward to. But he couldn’t bear it. His jar would be empty by the end of the day. Everyone in the surgery knew that.

When he once more turned his attention to the women, they coughed into their handkerchiefs and held thin hands to their foreheads. The children were pinched and poked, and a little boy burst out crying. Clara thought this a cruel way to get the doctor’s attention. She took a moment to examine the hole in her stocking, bending enough for the hem to rise that bit more up her thigh.

Voice neutral, Dr. Blum said, “Fräulein Müller.”

As she limped past him—she hadn’t limped coming in; it had only occurred to her now to begin—the women’s coughs grew hostile behind her.

Once they were alone, Dr. Blum scooped her up and sat her on the examining table. “You’re early, my sweet. We were supposed to meet at five.”

“I have to cancel. Oh, don’t look at me like that. So puppyish.”

She cupped his ears, soft and fragile, and kissed his wonderfully unremarkable face, one sharp cheek, then the other, and finally his chapped lips. He was a small man, shorter than she liked; they would be almost the same height if she stood with the posture she’d had in the war. Back then, the Allies had claimed an iron rod was fused to her spine. They had called her unnatural, part human, part machine. Punch did a caricature of her eating coal and drinking oil, with cogs for joints. She had framed it and hung it next to her office chair to remind herself of what she’d become to the outside world.

Dr. Blum knew nothing about all that.

“Darling,” she said, stroking his cheek, “I’m going to Essen for a few days.”

“You said you were going at the end of the month, for Christmas.”

“The weather is turning so fast. I thought I’d better go now for a short visit before the trains freeze to the tracks. I don’t want to get stranded somewhere.”

He looked skeptical, and it surprised her. He’d always been so understanding, so ready to listen. She’d first come to him complaining of weakness, a sudden darkness in her head, a weight pressing down on her so hard that she had to sit before she fainted. He prescribed pills that tasted of sugar, and foul concoctions that left an oily film in her throat. She’d had a touch of anemia, he told her. By then she knew the real diagnosis. Hunger, the national disease. For the first time in her life, she had gone hungry long enough for it to change her body down to the blood.

“Margarete, there’s something wrong. You’re very pale. I can tell by the shadows around your eyes that you haven’t been sleeping.”

She looked down at their hands, their fingers intertwined. “I’m just worried. Not about us, about my friend in Essen. I told you about Elisa, remember?”

“No, I’m not sure you did.”

“She hasn’t answered my letter. It’s been bothering me for weeks. I must go and see that she’s okay.”

“It can’t wait until Christmas? We have plans tonight.”

She explained again about the weather, and the days off work she’d negotiated with her employer, a cement factory where the management was astonished at her knowledge of production and logistics. She seemed too young, they told her, to know so much. She smiled modestly at that and mumbled about the valuable work experienc

e she’d had—in Essen.

“I’ll be back before you know it,” she said. “We’ll be able to spend Christmas together.”

Dr. Blum pulled away, ruffling his hair on the way to his desk. He yanked open the drawer, reached inside, and went back to her holding out his fists knuckles down. “Pick one.”

“Is it a peppermint?” She brightened. “A chocolate?”

He raised one eyebrow, a cockeyed look that made her smile. He wasn’t one for boyish humor, and she appreciated this side of him she hadn’t known was there. She tapped his left fist. He opened it finger by finger.

“Oh,” she said. “Oh my.”

In the lamplight, the ring in his palm shimmered darkly like old gold. It was a simple band without stones, and her hands went clammy when she looked at it.

“I wanted to do this tonight,” he said. “I’d gotten up the nerve—” He cleared his throat, began again. “Dear Margarete, I’m not a wealthy man.” From there, he outlined his finances, the expenses of the surgery, the reality of living in the rooms upstairs, how the war had wiped out his savings. “But you won’t go hungry,” he said. “I swear you won’t. We’ll manage to live honestly. We won’t be thieves or beggars like the rest.”

She was still looking at the ring. They’d known each other such a short time, most of it as doctor and patient. She wanted to ask him why the rush? But he was blushing and making so many promises about their life together, she didn’t have the heart to interrupt him.

“And I thought perhaps you could take over the bookkeeping,” he said. “You have a good head for that. The paperwork and the charts are a bit of a mess. I’ve been drowning since I lost my assistant.”

“Aha. You want the cheap labor?”

“Of course not.” He pressed her to his chest. “Although . . .”

She thumped him on the arm, more nervous than she let on. Marriage had been a delicate topic in her family and she was still uncomfortable with it. She tried to imagine Dr. Blum meeting her father. She was sure Papa would like him, this steady, reliable, generous man. She imagined them shaking hands for the first time, Dr. Blum’s respectful bow, Papa’s gesture to stop the formalities. They were family, and these were new times, he would say. A chance for a new life.

Doctor Blum. Herr Doctor Adolf Blum. His first name still made her squirm, but maybe she could call him . . . Adi. In every other way, he was perfect. A quiet man leading a quiet life in this little corner of Germany. He had no family or close friends. He avoided social engagements, as she did. He never read the papers, which had seemed strange at first, but then, hadn’t they all had enough of politics? When the radio announced news, he turned the dial to music. Polkas were his favorite. She had nothing to fear from a man who loved the polka.

She looked at the water stain on the ceiling, the cracked paint on the windowsill. She had never been in the rooms upstairs but could imagine them, dark and low and narrow. This house wasn’t much, but she began to imagine it with a fresh coat of paint, better furniture, a little care. She could fix it up, make it a place her father could stand to live in after he was released. A peaceful, comfortable place for him to recover out of the public eye. He was going to need that. It would be especially useful to have a doctor in the family. She imagined Papa moving in, having to hold his arm as he limped up the stairs, and she blinked at Dr. Blum to make the image go away.

“May I set a condition?” she asked.

Dr. Blum took off his spectacles. His eyes were watercolor blue. “Really?”

“Really.”

His kiss tasted like a warm sweet in her mouth. It was hard to pull away. “I don’t want any fuss about the wedding,” she said. “No announcements in the papers. A small ceremony, only witnesses.”

“Of course, whatever you like.”

Only one witness mattered, and that was Elisa. Clara wasn’t about to marry without her oldest friend there to weave her a bridal crown out of chewing gum wrappers, or give her advice about men. Two months ago, Clara had finally judged it was safe enough to send her a letter, but had heard nothing in return. It was likely the post was being as unreliable as everything these days. Or perhaps Elisa hadn’t wanted to write back, a real possibility considering Clara had left Essen at the end of the war without saying good-bye. At the time, she had thought it best if no one knew her plans. Elisa would not have had to lie under questioning, if it had come to that. But the silence over the past months was awful. Clara had begun to stock up on food and check almost daily on the train-line repairs that would allow her to get back to Essen. Just for a short trip. To see how Elisa and her son were doing, to apologize for leaving them so abruptly. Once she explained, Clara was sure Elisa would forgive her. And she could deliver her wedding invitation in person.

She turned the ring in her palm. When she married, she would make her home here in Hamelin, not in Essen. The thought felt strange. So final. But perhaps it was safer in the long run. “Oh, darling, there’s one other thing. There should be a photograph only for us. Nothing for friends or acquaintances.”

She expected Dr. Blum to demand an explanation. Instead he slid the ring onto her finger. Slowly. Pregnant with suggestion. “That suits me perfectly.”

They hugged, Clara not quite believing she was to be married. She hadn’t slept last night, and she feared she wasn’t thinking as clearly as she should. But it was warm in his arms, and she wanted the warmth to last a little longer. She hooked a finger in the waistband of his trousers. The shock on his face passed quickly, and then he pressed her hard against the table, urgent, almost desperate. She responded in kind, wanting him just as intensely. It had been years since she was with a man, and how dull that time had been. But then he ripped her stockings, a long tear she felt as a cold draft down her leg. She bit back a cry of surprise and indignation. Max would never have done that to her. She ground her teeth until her jaw ached, wanting Max gone—out of her mind. He shouldn’t ruin this moment. But he was still her standard by which all other men were measured. He had known how to blaze through her and leave her as groomed as when they began. Dr. Blum didn’t realize or care that she was going to have to walk out of the surgery looking like a tart who couldn’t keep her hosiery in one piece.

Looking pleased with himself, he gave her one last kiss, poured schnapps from his desk drawer into two mugs, and toasted their future as Herr and Frau Doctor Adolf Blum. “I’m so glad we’ve sorted this out,” he said. “Now we can drop the pretense.”

The electricity flashed on. Around the consulting room, overhead lights glinted on the scale, the tap, the instruments on the cart. Clara blinked the sparks out of her eyes, but they didn’t clear. They were in her head, insistent as an alarm.

“Don’t worry, I’ll be a good wife,” she said cautiously. “Old maids are motivated to learn.”

“Now, now, I’m serious.” He caught her hands in his, tighter than was comfortable. “We’re going to be married. Don’t you think we should talk? Be honest with each other?”

“Yes, of course.” She glanced at the door. “But you have patients . . .”

“They can wait. My dear, I’ve been bothered by . . . well, not doubts. I don’t doubt you. But I have questions. I hope you’ll answer them right now. Then we’ll start a new life, closer than we were before. Isn’t that what you want?”

Maybe this wasn’t going to be so bad. She had spoken very little of herself. Wasn’t it natural for a groom to want to know something about his bride? “Tell me what’s bothering you. We’ll clear it all up.”

He kissed her fingers. “These are complicated times. One must be careful, as you well know. When I decided to propose, I took the precaution of asking around about you.”

She freed her hands from his. “Spying? You were spying on me?”

“Learning about you, especially what you were like before we met. You took lodgings at the Hermann house soon after the war. Frau Hermann said you always wore a scarf over your hair.”

Frau Hermann, the old bu

sybody.

“Once, by chance, she glimpsed you without it. Your hair”—he touched the strands at her temple —“had just begun to grow back. It had been shaved.”

“I had lice, I’m afraid.” A lie. “I don’t like to remember those times.” The truth.

“Before you found work, you paid your rent on time without fail and never lacked for money. Where did you get it?”

“My family never believed in banks. We kept Reichsmarks under the mattress. When the war was ending—”

“Your family, yes. An important point.” Dr. Blum folded his stethoscope into his pocket. “You never speak of your family. Frau Hermann said you get no post from anyone named Müller and no visits at all.”

“The war, the Collapse, you know how hard it is to find people—”

“My dear, be honest. Are your parents alive?”

This was dangerous territory. It would be easier to say they were dead, but the thought alone opened up a vast well inside her.

“They’re all right. I think. I haven’t seen them since the war.”

“You quarreled with them?”

“No. No, not really.”

“Well, what then?”

She tried to think of an explanation he would believe. It was taking her too long, and his face grew grim. “Did they emigrate?”

“No, it’s not that. It’s more . . . they’re hard to reach.”

“If we’re to marry, I really should speak to your father.”

She searched his face for an ulterior motive and saw only the earnest wrinkle of his brow. Of course the bridegroom wanted to meet the father of the bride. But Dr. Blum was treading too closely to the very problem that had kept her up all night. She had lied to him; she had seen her father since the war: yesterday evening in a British newsmagazine she’d been surprised to find in her land-lady’s parlor. He was standing in front of what looked like a barracks, staring out of the photograph across two Allied zones directly at her.

She had smuggled the magazine up to her room and thrown herself onto her narrow bed before she had had the strength to examine the picture more closely. His coat billowed from his body as if he’d shrunk. Weren’t the Americans feeding him in their blasted internment camp? On his chin was the shadow of a beard. It was unheard of, this lack of grooming. The dome of his forehead was starred with light, sweating as the photograph was taken. It appalled her. Papa did not sweat. More deeply shocking was the puffiness of his face and the slight prominence of his eyelids. She had seen this swelling in Grandfather before his heart failed. Now she saw it in Papa.

The German Heiress

The German Heiress